My name’s Darren Tims, I’m a principal at Rice Daubney.

My name’s Darren Tims, I’m a principal at Rice Daubney.

I’m just going to show you a bit of a snapshot of some of the work we’ve been doing over the last number of years, particularly in relation to the way that we use technology in our practice and BIM.

So what I’m going to cover is who we are and what led us to BIM, what are the benefits of BIM and how we actually work and how we actually create what we do.

The Ark in BIM – and the Ark is a building that we’ve recently completed so it’s a bit of a case study – and just touch on some of the issues that relate to the future and what our industry really needs to grapple with.

So who are we and what led us to BIM?

We’re a major architectural practice based in Sydney but with a small office in Brisbane, about 105 people in total, and we work in the commercial, retail, health and research, and defense sectors of our industry.

In about 2001, we took a step back from our CAD software, which we’d had for a number of years, and really thought that we weren’t getting the best out of it.

How did we know that?

We knew that other industries were producing work like this, this is obviously the automotive industry, but we knew that the shipbuilding and other design industries, aircraft industries, were producing this kind of information.

We knew that it was possible to take the design and documentation from one model by virtual building, because our software vendor Graphisoft was telling us that, but we really weren’t doing that.

We also wanted to reduce some of our risk.

There’s a lot of things that an architect does that are high-risk, and it’s usually the more – if you like – boring things that we have to do within our profession.

There’s a lot of things that an architect does that are high-risk, and it’s usually the more – if you like – boring things that we have to do within our profession.

What you see here in the background is a precast concrete schedule that’s been automated from a model, and in the foreground we have a door-window schedule from a recent DER schools program.

We wanted to be producing what we call bulletproof documentation, and there have been a number of studies in our industry about the standard of documentation and its decline over the years.

We knew also that there was potential to reduce our risk and therefore increase our profitability in addition.

This is an image taken from, it’s a screenshot from a smart board in our office, we use this in consultant meetings, this is actually taking a DCA consultant through the model into an existing building that we’re adapting, to help him to understand in the third dimension the fire compartmentation in this building.

I spoke a bit before about the quality of documentation in our industry.

This is a report that was commissioned in 2005 by industry bodies in Queensland, it identified a number of problems in our industry in relation to documentation.

There are lots and lots of problems, just to reflect on a few of them: 60 to 90 percent of variations in our industry are due to poor design documentation, and that’s estimated to cost our industry around 12 billion dollars a year.

The worrying thing from this report is that at the time CSR said that standard was continuing to decline, and I’ve seen very in our industry that’s said that decline has halted or indeed has been reversed.

Some of the root causes that the report identified:

Inadequate use of CAD.

CAD really hasn’t delivered, in my view, very much for our industry in the last 20 or so years.

We really took on a piece of technology that simply replicated what we had been doing for hundreds of years, and that’s drawing two-dimensional lines, in this case electronically instead of on a piece of paper.

There’s also a direct correlation to a reduction in fees.

I don’t think that’s entirely about being part of a competitive market, though that’s obviously part of the problem.

But also procurement methods have changed in the last 12-15 years, particularly the introduction of design and construct contracts, which probably 90 percent of our work falls under.

So all that means that we need to get really smart about the way we use technology, the way we collaborate and work together as an industry.

This is a diagram that the CRC, a government funded research body until the end of December, and the Institute of architects got together and collaborated on to produce really for our industry so that we could understand the different stages of BIM.

This is a diagram that the CRC, a government funded research body until the end of December, and the Institute of architects got together and collaborated on to produce really for our industry so that we could understand the different stages of BIM.

At the bottom you’ll see a bell curve with the word Uptake on it, that’s really where the Institute felt that the majority of our industry was working.

Very much in the intelligent 3D realm.

We don’t believe that that’s true; we actually think that most of our industry are very much still working in 2D CAD;

there is undoubtedly people pushing into the 3D realm and working in 3D and there are also people doing great stuff with BIM as well.

What I’m going to talk to you about is Liverpool hospital predominantly, and also the Ark.

The Liverpool Hospital started very much as a one-way translation, we were delivering models to other consultants, we are now getting models back, not from consultants in this case but from subcontractors, D&C subcontractors;

and I’m also going to talk about the Ark as a bit of a case study.

The Ark is very much a two-way translation of models, it was set up as a BIM project from the beginning, we managed to convince the investor to take that leap of faith back in about 2006, and we’ve now delivered on that with an as-built BIM which I will show you.

The dotted line really represents about as far as I believe you can go today.

And that’s really based around a couple of things, model server technologies, still have a little bit of work to do in our view, and also there are some legal and liability issues that our industry needs to grapple with, which again I’ll touch on a little later.

Just to give you an idea of Rice Daubney’s journey with BIM:

we purchased ArchiCAD in about 1995, we previously before that had a piece of CAD software called JVS, so we were very much working in a manual 2D realm and a 2D CAD realm right up until, as I said earlier, around 2001.

At that point we took our switch to 3D, we did a pilot project in 2001 and in 2002 mandated 3D for all our projects across the practice.

And as you can see from the arrows on the bottom, we’re now very much into the one-way and two-way translation of models.

So we’re now at a point in time, and I think our industry’s at a point in time, when 3D is quite mature, we’re now very much moving into the realm of BIM.

And that’s really where we’re heading and that’s what I want to show you today.

So what are some of the benefits of BIM?

We believe that you get very much better design from using BIM and that’s largely because we’re making a lot of design decisions earlier.

What you’re seeing here is a cut-through of a project of ours.

That section is through the same model, so it’s just really being shown in different ways, it’s being graphically presented at the bottom of this slide to show a client a visualization of the room, in this case obviously the lecture theater, and at the top of the slide is graphically represented as the drawing that a builder can build off.

But they are both from exactly the same model, cut in exactly the same place in that model.

So you can see the level of detail that goes into these models, and that’s really why we’re getting better design.

We’re having to make a lot of design decisions much earlier in the process.

We have better control and consistency over our QA processes and therefore, for us, less risk.

This is a shot, an extract of the model from Liverpool Hospital.

The red walls that you can see in this hospital are fire compartment walls, and the green walls are acoustic walls.

When this model is passed over to a subcontractor and he’s running ductwork and pipework around the building, he knows that when he hits one of those red walls he needs to think about fire dampers and fire collars.

So it’s very intuitive for him.

Similarly, when this drawing is printed out in 2D it’s printed in color, and those walls are represented in color.

So when someone’s jack-hammering a wall on site and looks at this drawing and sees that it’s a red wall, he understands that he’s now breaking through a fire compartment and he needs to address that issue.

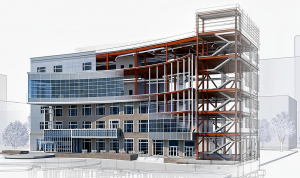

This is a snapshot from the Ark looking down on top of the building, straight down the core of a 20-something story building, and you can see all the structure and architecture have been turned off, this is just the services.

You can see how complex this is and you can see how being able to work in 3D improves the coordination process for us, both pre-tender, but also with subcontractors, and that’s very important in term of our collaboration on site.

We believe we have better staff attraction and certainly better staff retention.

Most kids today coming out of uni are being taught in 3D at the uni.

We’re now starting to see the first generations of architects that have only ever known 3D.

They want the latest iphone, they want the latest DVD player, they want the latest piece of technology, and they’re going to want to work with the latest technology, and that’s certainly part of the reason that we work this way.

We also believe that we’re improving the construction knowledge of our staff.

What you see here is a number of shots within a single model, but you can see when you strip down that model there are studs being drawn, there are top hats being drawn, there are gaskets being drawn between glazing and cladding, there’s a plan in the middle of that diagram which is traditionally what a builder would have got.

Our staff are virtually building, they are starting to understand what they are asking builders to do on the site, and they are certainly gaining better construction knowledge through the process.

We’re certainly getting better communication, not just with our clients – I think that’s an obvious one from the point of view of visualizations.

Again, this is a screenshot from our smart board, these images get attached to minutes of consultant meetings.

In this image, we’re trying to convince a mechanical consultant that his ductwork can’t go on the ceiling of this building.

So he’s working in 2D, we’ve modeled his major duct runs which you can see in color at the top in red and yellow and blue, and we’re really working on the smart board live in our model to show him that he needs to be feeding his air through the floor and not in the ceiling void because there is no ceiling void.

He really couldn’t grasp that from the two-dimensional perspective.

We believe also that we’re getting improved productivity from the way that we’re working, and hence, for us, improved profitability.

At the end of the day, we’re a business and we need to show a return on the work that we do and the commitment that we make to technology.

So how do we actually work?

So how do we actually work?

Right from the master planning stage, we start our BIM models.

What you’re seeing here is the staging model for Liverpool Hospital which I’m going to talk about in a little while.

The colors obviously represent the different stages.

But at this stage we can look at this building in an urban environment.

That’s really important for buildings like this that are campus type buildings, how they relate to their surroundings.

We can do shadow studies from these models at this stage.

We can take initial quantities off, we can take initial areas off, and therefore clients can get budget costs even from this very early stage.

So it’s still starting to build information into the model and that’s really what the models are about, being information-rich, and capturing that knowledge now right from the start of the process.

We work in a number of ways, we still have paper, we use butter paper, that’s absolutely valid in the way that we work.

We also use SketchUp, which is what you can see here for initial modeling of our buildings.

You can see that same building that then gets translated into ArchiCAD, and obviously a level of data is now being started to add, and ultimately that becomes a visualization which is used for submissions for DA, or obviously for clients and to attract potential tenants.

We have a number of methods of doing visualizations.

This is the PPP bid for a hospital, unfortunately we didn’t win, but this is a very big building, a $750 million development, and this was documented fully in 3D to quite a decent level with the Ff&E included, in about six months.

We also use Artlantis: Artlantis is a great plug-in for us, it does lots of what we call quick and dirty images.

All our project teams are capable of producing these quick images, to sell to clients what we’re trying to do.

Here you can see some examples of some DA documents that we’ve recently submitted.

I spoke earlier about how much more information we’re putting into our models, and the design decisions we’re making earlier.